Atlanta Weekly December 5, 1982 pg. (courtesy Miller Francis)

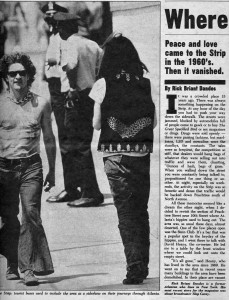

Peace and love came to the Strip in the 1960’s. Then it vanished.

By Rick Briant Dandes

Rick Briant Dandes is a former Atlantan who lives in New York. His most recent story for the magazine was about broadcaster Skip Caray.

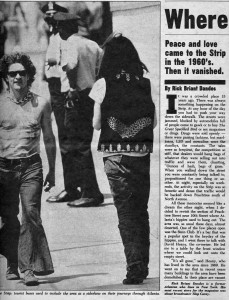

It was a crowded place 15 years ago. There was always something happening on the Strip. At any hour of the day you had to push your way down the sidewalk. The streets were jammed, blocked by automobiles full of people come to gawk or to buy The Great Speckled Bird or sex magazines or drugs. Drugs were sold openly — there were passing fashions, but marijuana, LSD and mescaline were the standbys, the constants. The sales were so frequent, the competition so stiff, that dealers would hang bags of whatever they were selling out into traffic and wave them, chanting, “Ounces of hash, bags of grass.” When you walked down the street you were constantly being talked to, propositioned or one thing or another. At night, especially on weekends, the activity on the Strip was so frenetic and dense that traffic would be backed down Peachtree south of North Avenue.

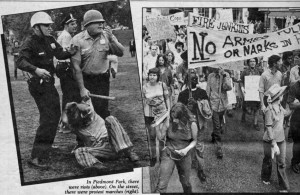

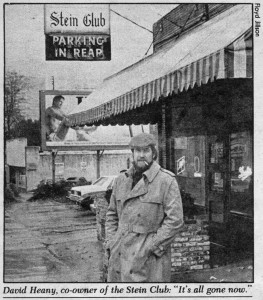

All these memories seemed like a dream the other night, when I decided to revisit the section of Peachtree Street near 10th Street where Atlanta’s hippies used to hang out. The area was, as usual these days, almost deserted. One of the few places open was the Stein Club. It’s a bar that was a popular spot in the heyday of the hippies, and I went there to talk with David Heany, the co-owner. He led me to a table by the front window where we could look out onto the empty street.

“It’s all gone,” said Heany, who has lived in the area since 1969. He went on to say that in recent years many buildings in the area have been demolished. In their place are vacant lots, construction sites and condominiums. “It’s the midtown boom,” he said sarcastically.

It was 9:00 p. m. and in the bar about 50 customers were milling around. Heany pointed to one, a social worker named Karen, he said, a regular at the Stein Club for almost as long as it has existed, 21 years. Karen sat alone, sipping from a mug of beer as she leafed through a note pad. I don’t know how Heany recognized her. She was, for all intents, incognito, like a young Greta Garbo, dressed in a’ black silk blouse and prairie-length dress. Her hair was wrapped in a scarf, her eyes hidden behind wraparound sunglasses.

“She was a hippie,” Heany said, taking me over to meet her.

“I lived down here when this entire area was overrun with young people,” Karen said. “It was a good time to be young, those years. I learned so much about life. It was exciting. I think I knew it couldn’t last forever, my youth I mean. But I still sometimes wonder what happened down here, why everyone left.”

“A harder element moved in, Heany said. “I remember when it turned into a rough neighborhood. You couldn’t walk a block without -being propositioned for anything you could imagine, drugs, sex. Whatever you wanted to buy, it was for sale. When the hippies left, the Strip became a no-man’s-land. There was a lot of arson. Businesses that had been here for a decade moved out. I remember in 1974, walking down the street and in a three-block area there were only 11 shops open. It really scared me.”

“That’s the real question,” Karen said. “How did this area go from hippie community to combat zone to middle class — which is what it is becoming.”

Heany nodded agreement. “I wish I knew what happened during those hippie years. I lived here, but I’ll be damned if I know.”

The Hippies overran a neighborhood that was steeped in Atlanta lore and history. Full of old houses, it had grown up around Piedmont Park to become a showcase middle-class neighborhood. In the earliest days of the city, however, the neighborhood around what was to become the Strip — an area roughly bordered by the park on the east, 14th Street on the north. Spring Street on the west and 7th Street on the south — was called Tight Squeeze.

“In the 1870’s, it was well beyond the city,” according to historian Timothy Crimmins of Georgia State University. “Peachtree Road didn’t follow its present course back then, it followed the route of what is now Peachtree Place to 11th Street, so it was much narrower. It was, though, a main route of commerce into Atlanta, and so as you were going out from the city, you were tunneled in through this narrow neck of road. Shanties were erected alongside the route. “Late in the 1890’s the shanties were pushed out,” continued Crimmins. “As long as there was no demand for the land, the squatters who lived there had no problems, but with the development of streetcar transportation, the entire area came within the orbit of Atlanta, and at that point it became a more desirable place for affluent Atlantans to live.”

As the trolley moved north in the early 20th century, large Victorian homes were erected by the city’s wealthy elite, and in 1906, Ansley Park was developed north of 10th Street. Soon there was a demand for commercial services, and 10th and Peachtree became the intersection where they were provided. By the early 1920s drugstores, bakeries, bicycle and dress shops fined I0th Street.

During and after World War II, there was a lot of pressure for housing in the area, and many of the buildings were eventually zoned as multifamily residences. In the 1950’s, however, there was a wholesale northward exodus of residents. This effectively set the stage for the 1960’s, creating an area with relatively inexpensive housing around a commercial strip where the market had declined, leaving empty, low rent storefronts.

The counterculture had I its origins in San Francisco at about the same time the civil rights movement peaked in the South. By the time the hippies appeared in Atlanta, the Strip was where the “life” was, in the words of many who lived there. Filmmaker Gary Moss, who later chronicled his experiences on the Strip in a movie entitled Summer of Low, remembered leaving the University of Georgia and moving to the area in 1967. “I knew something was happening, even if I didn’t know what it was,” he said. “I had friends who

lived on 9th Street, and I’d visit them and see an entirely new attitude in how they talked and looked. I was fascinated, and found myself being drawn into the life. It was just very exciting to be down there. We had freedom, and to some extent we had drugs, mainly marijuana. It was a playful time, sad, of course, we were learning about love and sex.”

In 1967, the number, of hippies living in the neighborhood was still small, perhaps a few hundred. (By August 1969, according to a Community Council of Atlanta report, the number of hippies living in the 10th Street area was estimated at 3,000.) Yet they had great visibility, making themselves instantly recognizable by characteristics that seemed intended to stun — long hair, for example, and instead of conventional dress, fantasy garb as different and unique as could be found: old hats, long dresses and shawls. In a way, dress was a nonverbal dialect created by hippies as a way not only to recognize each other but to keep at bay the curious in straight society.

The new community took seed at the Mandoria, an art gallery owned by David Braden (“Mother David”) and Kathryn Palmer, a jeweler. In late 1966, Braden and Palmer moved their gallery into a two-story house at the corner of 14th and Peachtree streets, across from what is now Colony Square. In the basement of the house was a music club called the Catacombs (“A place for peace and creation,” read early ads). Above the Mandoria, Braden rented out beds to people coming into Atlanta, many of whom were runaways.

“There was a verbal network, and word got out that there was a place to stay at Mother David’s,” recalled Anna Belle Illien, who purchased the gallery from Braden and changed the name to Galerie Illien. “Beds were rented in shifts, there were so many kids. I heard there was once as many as 50 people upstairs at one time.”

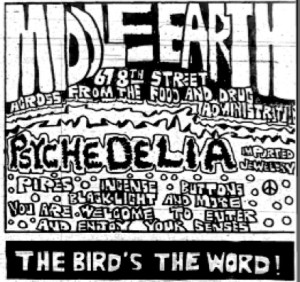

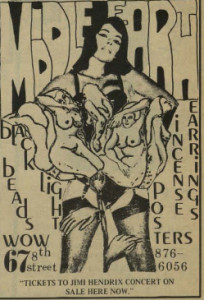

Braden eventually landed in prison (serving a seven year sentence for marijuana sale, his arrest was generally regarded as the area’s first political bust), but the scene kept on growing. It was centered at 10th Street around new hip establishments like the Twelfth Gate (a folk-music club operated by a young minister, Bruce Donnelly), the Middle Earth, Grand Central Station, the Merry Go Round and Morning Glory Seed — Atlanta’s first “head shop.”

Along with the clubs, other expressions of the scene began springing up. One of the most important was The Great Speckled Bird, a weekly newspaper. Its first issue came out on March 15, 1968, and the paper rapidly became the voice of the community. About the same time. Dr. Joseph Hertell, a former national director of the American Red Cross, was teaching Sunday school at Rock Springs Presbyterian Church when he “noticed a good many of my students spending time at the Twelfth Gate cafe. My wife and I went down there, met Bruce Donnelly and saw that the club was spiritually oriented — he held services every Sunday It was a very warm and pleasant atmosphere.”

Dr. Hertell asked Donnelly if he could help in any way and the minister told him, “There is no place for sick kids to get help. When I have a sick youngster on my hands, I can’t get any help — not even from Grady.” That’s when Dr. Hertell and Donnelly opened a clinic in a back room of the Twelfth Gate (the clinic later moved to Juniper Street).

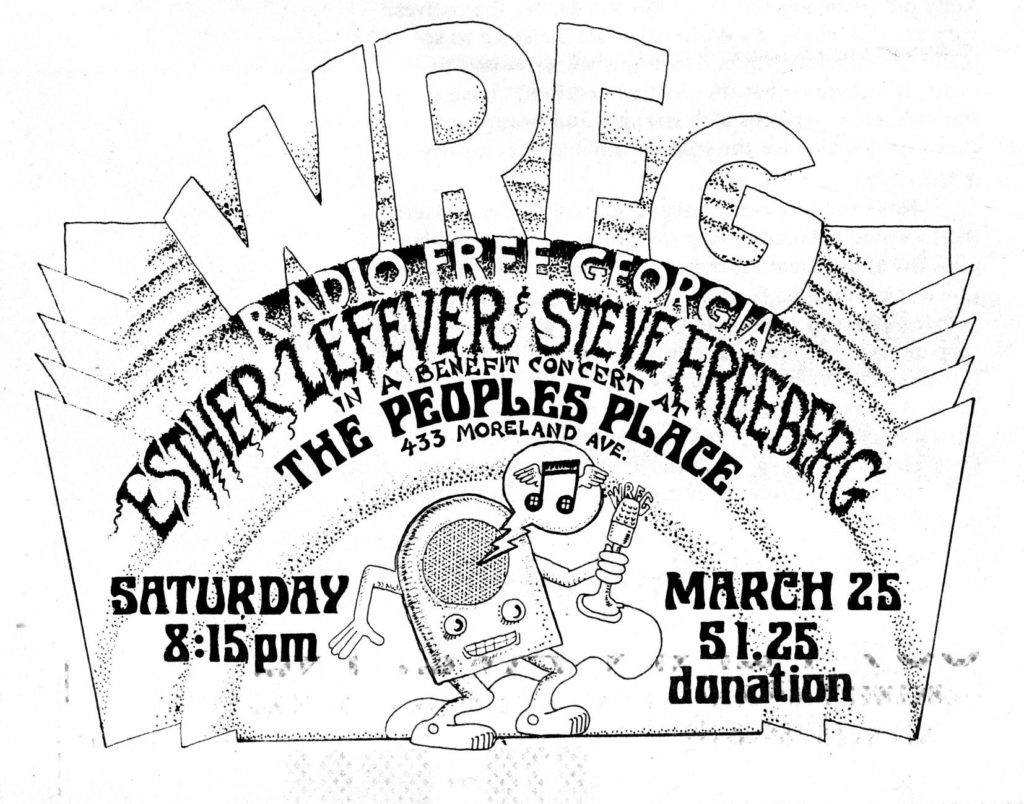

Music was everywhere back then. Nasty Lord John, a disc jockey at WBAD in Hapeville (Atlanta’s first true progressive radio station), was also a musician, a drummer in a band that played at a club called the Scene, and listeners followed him to the Strip. “His radio show turned me on,” said Darryl Rhoades, a longtime local musician. “I wanted to see him. When I was in high school, he was a topic of conversation. Music was a big reason to go to 10th Street.”

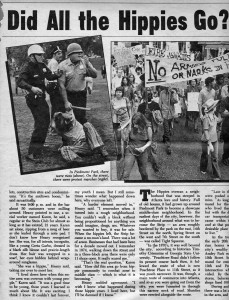

At the Scene, Twelfth Gate and the Catacombs, bands like the Bag, Hampton Grease Band and Dr. Espina’s Banana Boat Blues Band and Traveling Freak Show were big attractions. Rhoades himself played in a band called the Celestial Voluptuous Banana. Concerts in Piedmont Park were common, with local bands playing alongside The Allman Brothers, The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Cream.

By the summer of 1969, young people from all over Georgia and the rest of the South were coming to Atlanta. Many of them joined communes, which were characterized by their informal living arrangements and the sharing of property. This eventually created problems, according to Mary Huffaker, a social worker in the community. “Every single commune I know anything about failed because they would accept anybody and everybody,” she said. “Obviously. you’d get freeloaders who were happy to sit back and watch everybody work except them. The fact is, communes couldn’t work if everyone didn’t pull his own weight — and the nature of human beings is that they don’t.”

(old French embassy on 14th)

Eventually the police became a major factor on the Strip. Tension had always existed between hippies and the police. Fulton County Assistant Police Chief Lewis Graham, then an Atlanta homicide investigator, recalled a “strong dislike of them on the force. The average police officer saw traditional values disappearing — kids with long hair, beards and their up-front attitudes. Most officers wouldn’t allow themselves to believe that many hippies were good kids with educations. They were simply classified as bums, identified by how they dressed, how they looked.”

Nonetheless, a kind of peace existed between hippies and the police for a while, and at least one officer was different — Ray Pate, who was assigned to community relations on the Strip. Pate was never given instructions on what to do or where to work. “I had no hours,” he recalled, “but I worked 9:00 p. m. to 5:00 a. m. in the park, at the clubs. I tried to identify with the youngsters. I wanted them to realize that cops are human, too, that they could depend on me if they needed help.”

The problem in the early days, according to Pate, “was mainly with shop owners who saw the values of their businesses depreciating. People were being driven to bankruptcy.” At times, pedestrian traffic in the area was so heavy that people walked in the streets. Tour buses included the Strip as a sideshow in their journey through Atlanta.

Some area store owners do not blame the hippies for their problems in the 1960’s. Mike Roberts of the Hard ware and Supply Company said, “In my opinion, it wasn’t the hippies who ran the area down. I think the area was already in decline by 1965, when shopping centers in the suburbs were built.”

By all accounts, the winter of 1969-1970 was a turning point in the history of the Strip. Pate remembered that “in late 1969, things took a nose dive. It was a cold winter. Everyone stayed indoors. The streets were relatively empty, and by spring it seemed almost like a small child had grown up and turned mean. Maybe the kids realized they had to survive somehow, find food — and soon. But it wasn’t the same and I couldn’t put my finger on why.”

Dr. Hertell also sensed a change in the neighborhood. “Disillusionment had already set in,” he said. “The love, the fraternity, the beauty and the warmth was souring.” Dr. Hertell and others believe that the increasing drug traffic up and down the Strip — and the change from marijuana to harder drugs like amphetamines and heroin — led to the community’s downfall.

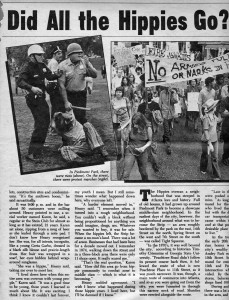

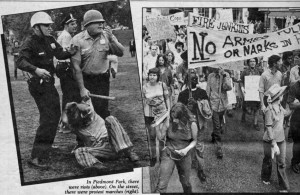

With harder drugs on thy streets, the police cracked down on the community. Pate explained, “In 1968, we were flooded with crowds of exuberant, music-loving kids. We couldn’t do things the old law-and-order way with them •— the media would have killed us. But in 1969, with the criminal element moving in, well, those were our kind of people, so we flooded the area with helmets and nightsticks.” In 1970, Police Chief Herbert Jenkins declared, “I’m convinced 10th Street is no longer a hippie community. It’s just a stopping place for outlaws and criminals from all over the nation.”

The police raids were awesome, in a chilling kind of way. On weekends, police would arrive on the Strip after midnight in school buses. They would stream out of the vehicles in riot gear and move down the street in formation, stopping in front of each storefront while several went in and cleared the kids out with billy clubs.

One of the biggest events of this period occurred on the night of October 4, 1971 That was when a policeman was shot in Piedmont Park on “hit-up hill,” an area near the pavilion used by drug peddlers. A man who lived on 11th Street at the time remembered being awakened “by all the light and noise. I looked out the front door to see throngs of people screaming and running up the hill to Peachtree. Overhead, herding them like cattle, were helicopters with bright floodlights and loudspeakers blaring. The police entered every apartment on the park that night and turned them over.” (Soon after that incident, horse patrols were instituted by the city as a way to deal with policing the park.)

By then, the community was in chaos on all levels. Dr. Hertell’s clinic was treating more and more heroin addicts, and it eventually came under police surveillance as a result of its methadone program. “The police said I was responsible for more methadone being out on the streets than any drug pusher,” Dr. Hertell said. Its work with addicts also brought the clinic into contact with motorcycle gangs. “The bikers were power hungry,” said Dr. Hertell. “They came to me one day and said, ‘We want the clinic open tonight.’ I said I wouldn’t do it. Well, they took over because of their violent nature.” Mary Huffaker said that such incidents finally caused the clinic to close. “We didn’t know how to deal with violence.”

Along with hard drugs, the Strip was spawning an increasing number of pornographic bookstores, X-rated movie theaters and strip joints. Prostitution was on the rise. Gary Moss, who left the area for a few years, remembered coming back in 1972. “That’s when I realized the scene had grown dark and ugly,” he said. “I ran into an old friend with whom I had lived in a commune, and we Stopped and talked for a minute. She indicated to me that occasionally people came by and gave her money for sex. I sensed she was burned-out inside. She said she had had a vision in which trees burned down like match sticks.”

The Strip was literally burning down. A shop named Atlantis Rising had been firebombed, and The Great Speckled Bird house on 14th Street was destroyed in a fire. As early as July 1969 the Atlanta Fire Bureau reported 26 “significant” fires in the area causing $800,000 damage. At the time. Chief J. I. Gibson said it “looks like the work of an arsonist.” Indeed, arson grew rampant along the Strip. Houses were frequently burned as vengeance in bad drug deals. And a fire investigator said, “We hear that one small store owner paid well to bum up his unbreakable lease.” Many businesses, unable to get fire insurance, were forced to relocate.

Rumors persist to this day regarding the decline of the Strip during the early 1970’s. At the time, it was common knowledge that the Colony Square project and the planned MARTA station at 10th Street would change the face of the area. Many people in the community believed — and still do — that the Strip was intentionally allowed to deteriorate, thereby lowering land values, permitting real estate speculators to purchase plots at deflated prices before reselling them to developers at huge profits.

Many of these rumors center on former Mayor Sam Massell. He and other members of his family own land in the area, and Massell is familiar with the charges against him. “One rumor,” he said, “was that I was bringing the hippies into the area, importing them, in order to run down the values of the property, or that I had gotten options on lots, then allowed the property values to run down and buy in. Well, of course, if you had options on land, you’d have them at current prices, not run-down prices. Secondly, if you didn’t have the option, anyone could get the same option and buy it when land value decreased. And thirdly, if you did allow the land to run down, look at what it takes to build it back up.”

Unquestionably, land speculators in the area did make money. Some lots were sold in the early 1970’s, when land values were deflated, and a few years later they were resold at a profit to developers. However, no decisive relationship between the decline of the Strip and profits derived from it can be proved.

The real story behind the passing of the hippies from the Strip probably lies elsewhere, but nobody really has any clear-cut theories. Any discussion of the community by people close to it is, inevitably, suffused with a sense of wistful regret. As Dr. Hertell put it, “1967 and 1968 were beautiful. The kids were so filled with love, and it was so sad because what the hippies believed in was impossible. I knew it was impossible, and I felt like saying, life is not like this, life isn’t this way. They had a dream, and I’ve lived long enough to know that the dream wasn’t going to come true.”

But there was more behind the rise of the hippies than simply a dream. In their way, they mounted a strong protest against society. For many Americans, the Vietnam War represented a failure of the system, and the hippies were out to change it. As Charles A. Reich wrote in The Greening of America, an enormously influential book that articulated the hippie ethic, “There is a revolution coming. It will not be like ‘ revolutions of the past. It will originate with the individual and with culture, and it will change the political structure only as its final act It will not require violence to succeed, and it cannot be successfully resisted by violence. This is the revolution of the new generation.”

That sounds quaint and overblown today, but it was a potent message when it was first delivered. And across the country, it drew young people? pie to places like the Strip. They thought they were joining a revolution, but it’s my guess that in the long run they were just loose, on the run and lost. When I think honestly about the Strip, I remember that most of the people there were incredibly young. They were teenagers. So many of the girls were pregnant, and the boys seemed desperate. But they didn’t have any bona fide political convictions to back them up.

A friend of mine recalled an incident that pointed up the contradictions that haunted the Strip. “One day,” he said, “everybody on the Strip, went ga-ga over a car that was driving up Peachtree. It was a new Lincoln Continental, one with an arch in the back trunk hood for a spare tire. That would have been properly disdained in any truly revolutionary environment for good political reasons. On the Strip, the flower children rubbernecked and whistled.”

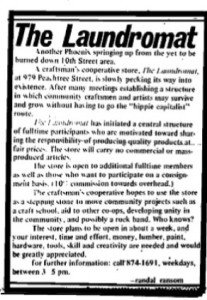

Craftspeople sold what they made through the Laundromat Co-op on Peachtree at 10th.

Craftspeople sold what they made through the Laundromat Co-op on Peachtree at 10th.