Atlanta Constitution Magazine June 9, 1968 pg. 24

The Twelfth Gate is a church for turned-on types. Coffeehouse Preach-In

By Olive Ann Burns (note the wonderful Southern author)

THERE’LL be a preach-in and love feast at Piedmont Park this afternoon if it doesn’t rain.

THERE’LL be a preach-in and love feast at Piedmont Park this afternoon if it doesn’t rain.

The crowd will gather at 12:30, as usual on Sundays, at The Twelfth Gate, 36 Tenth St. NW, an old two-story green house with red, gold, blue, pink and tan trim, like straight out of a storybook, man.

If we have a great big beautiful day, the community of worshippers—many of them as bearded as the early Christians—will walk eight blocks together to Piedmont Park for a be-in by the lake. In full view of the park’s usual Sunday population of ballplayers, bird watchers, lovers and picnickers, The Coffeehouse Church will begin its celebration of worship by reading aloud:

“We gather as we live, in the Name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit . . .. 0 Lord, we confess our slowness to see the good in our brothers, the evil in ourselves.

“We gather as we live, in the Name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit . . .. 0 Lord, we confess our slowness to see the good in our brothers, the evil in ourselves.

And this is the one objective and ever lasting truth—in Jesus Christ our sins are forgiven. May we receive the gift and live . . ..”

A handsome, dark-eyed young Methodist minister will preach the sermon—the Rev. Bruce Donnelly, who speaks straight from the hip about the fact that for thousands years “turned-on types have experienced religious highs—visions and trips even—without the aid of mind-expanding drugs.” He talks about what’s wrong with straight society and what’s wrong with hippies, about what it means to be free: Free to love God, free to give, free to be sincere, not hung-up in guilts, fears or prejudices.

Even without a tie, the Rev. Donne looks like a product of straight society, which he is. He grew up as a Methodist Youth Fellowship leader at Peachtree Road Methodist Church in Buckhead, was president of his fraternity at Emory University and three years ago married a lovely straight-type Agnes Scott College graduate named Barbara Chambers. But he digs the needs of the artsy, folksy, craftsy types among the 25,000 unmarried young adults who live in Atlanta’s 10th Street area.

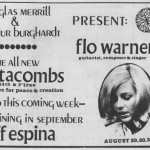

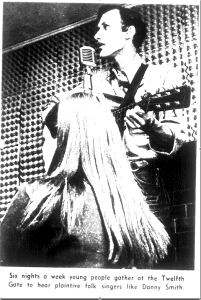

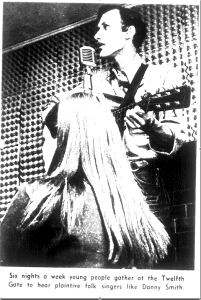

Bruce’s thing is The Twelfth Gate: On Sundays a religious community, the rest of the week a coffeehouse A place to talk play chess, buy a girl a gift. take a free course—in ESP or leathercraft, yogi-style meditating or the parables of Jesus—or sit over coffee and salami in rapt silence while the folk singers do their thing with songs like “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’ or “Isn’t It a Drag That People Take Tranquilizers “

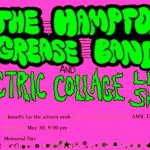

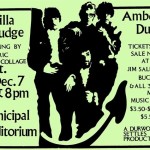

THE house opens every night at 8. The music starts at 9 Cover charge 50 cents or a dollar. No LSD. no pot, no beer, no whisky, no crash-pad, no nightclub-types jokes, no go-go. You could take visiting preachers, fifth-grade Girl Scouts or sheltered teen-agers there for the music and find nothing objectionable—unless you object to beards, candle light, red walls, satirical posters, a heavy fog of cigarette smoke or jokes about “kids on pot today, speed yesterday and acid the day before, but if you mention a cocktail, man, they wouldn’t touch the stuff, and that’s what I call hip-pocrisy. “

Unlike some other coffeehouses, the only pot available at The Gate is the kind that holds 50 cents worth of exotic coffee or tea. Jasmine and Himalayan Darjeeling have to compete with Georgia sassafras, brewed for the coffeehouse by a red-bearded folk singer who was once an Eagle Scout and got expelled from college for joining the march on Selma.

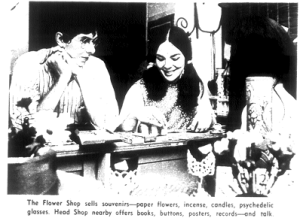

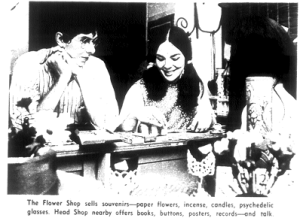

THE upstairs Head Shop sells no water pipes, roll-your-own cigarette papers or other equipment for smoking pot. It merely has folk records, books, posters, horoscopes, and lapel buttons that say, “God Is Alive and Well in Mexico City” or “Keep the X in Xmas.” In the Flower Shop, also upstairs, you can buy trappings of the hippie subculture—candles, beads. Incense (10 cents a stick), metal crosses hung on thongs, psychedelic sunglasses, and paper flowers. But there’s nothing weirdo about paper flowers when you find out they were made by student nurses at Georgia Baptist Hospital.

THE upstairs Head Shop sells no water pipes, roll-your-own cigarette papers or other equipment for smoking pot. It merely has folk records, books, posters, horoscopes, and lapel buttons that say, “God Is Alive and Well in Mexico City” or “Keep the X in Xmas.” In the Flower Shop, also upstairs, you can buy trappings of the hippie subculture—candles, beads. Incense (10 cents a stick), metal crosses hung on thongs, psychedelic sunglasses, and paper flowers. But there’s nothing weirdo about paper flowers when you find out they were made by student nurses at Georgia Baptist Hospital.

What’s so great about flowers” “They’re a symbol of beauty and peace, you never see one flower fighting another flower.” explained Brenda Brantly, the 23-year-old very unhippie engineering data clerk who is chairman of The Coffeehouse Church’s official board. Brenda came to Atlanta from Milner, Ga., and has surely seen a honeysuckle vine smothering a rose bush, but that’s what she said.

Despite all the beards, beads and sandals. The Twelfth Gate is too straight for most hippies. “I think I’ve finally convinced my father,” said Brenda. “that the kids here just aren’t interested in freaking out.” The working girls and boys, the college and trade-school kids and student nurses who patronize The Gate turn on with poetry, folk songs, art or religion, not with drugs.

Yet a Georgia Tech sorority refused to initiate a pledge when the members learned she’d been going there, and a lot of parents can’t believe any coffeehouse on 10th Street could really be nice.

“Part of the problem.” said Bruce. “is newspaper articles that call this a hippie house and label me as a minister to mixed-up kids. Also there’s the public notion that anybody who has a chin growth or long hair or sings folk songs is a hippie. This is just not a hippie thing. We’ve had no trouble with kids trying to take drugs here. Those who come are bright, turned on to life, with a great depth and capacity for enjoyment. But most of them have too much sense to risk damage from LSD or a police record from marijuana. If you say the sun is beautiful today, they don’t automatically think, “Yeah, but it would be really great under grass.”

“Sure. some of the kids have problems, especially with money. Most of those who left home because of family conflicts—or to be on their own were told by mommy and daddy, “Okay, you won’t live with us, we won’t send .you to college or pay your rent.” But they’re working out their problems in responsible ways. And they run this place responsibly. It’s the only church of 18 to 25-year-olds anywhere, that I know of, and we’ve never been late with a bill. Out of coffeehouse profits we pay me, we pay rent and overhead. We spent $2,500 this year sending three students to art school, and we’ll do that again next year. We’ll also give $3,300 to the Methodist inner-city ministry here. This inter-city program will pay my salary beginning in July, but the kids will then pay a manager—a soldier at Ft Mac named Pete Schoen. He’s getting out of service soon and will take over buying groceries, booking folk singers -and-running the staff, so I can have more time for running the church and counseling.”

“Sure. some of the kids have problems, especially with money. Most of those who left home because of family conflicts—or to be on their own were told by mommy and daddy, “Okay, you won’t live with us, we won’t send .you to college or pay your rent.” But they’re working out their problems in responsible ways. And they run this place responsibly. It’s the only church of 18 to 25-year-olds anywhere, that I know of, and we’ve never been late with a bill. Out of coffeehouse profits we pay me, we pay rent and overhead. We spent $2,500 this year sending three students to art school, and we’ll do that again next year. We’ll also give $3,300 to the Methodist inner-city ministry here. This inter-city program will pay my salary beginning in July, but the kids will then pay a manager—a soldier at Ft Mac named Pete Schoen. He’s getting out of service soon and will take over buying groceries, booking folk singers -and-running the staff, so I can have more time for running the church and counseling.”

MOST of the kids who come to The Twelfth Gate are between 18 and 25. (Bruce is 26.) Most of Atlanta’s hippies are just 13 to 17.

“There are only about 250 of these bubble-gum hippies and teeny-boppers in the 10th Street area,” said the young minister, “I’m talking about the ones whose life-style includes philosophizing, sharing what they have, not working at regular jobs. I’m talking about resident hippies, right? I don’t mean the 2,000 kids under 18 who hit Atlanta last summer.

“The vacation hippies fell in three categories: Those having trouble at home, those who wanted to see what it’s like to be on their own, and a minority who came for thrills—for sex and drugs and the glamour of running away.

“They came from all over the South, but a lot of the summer kids. were runaways from $50,000 homes in the Atlanta suburbs. Some stopped shaving, mussed their hair, went dirty, wore beads swiped from mom, stood on the corner of 14th and Peachtree to get stared at and learned to say would you be-in to a cup of coffee. To them everything was psychedelic, man, meaning colored lights, not consciousness-expanding. But most of them went back home after two or three weeks—when they got sick or real hungry, or maybe it was time for school to start. Unfortunately, a lot of the thrill-seekers went home really messed up on LSD—or VD.”

According to Bruce, the word is out that Atlanta is where it’s at this summer, man, the place to be: “Some think we can expect 16,000 to 18,000 between 13 and 15 years old. The out of-towners think Atlanta won’t lock up or run out that many. Well, Atlanta will. If 18,000 come, 16, 000 will soon leave. The problems of runaways aren’t solved by police harassment, but this city is just not equipped to take care of a big migration of teen-agers.”

A lot of parents and policemen call The Gate about runaways, from as far away as California and Idaho. One month Bruce located 20 kids out of 90 calls. “But I don’t really have much time. I often drop by the crash-pads or apartments where hippies live when the coffeehouse closes at midnight, and some hippies come to our church service on Sunday. But the heartache is that I’m not really helping these younger kids and nobody else in Atlanta is. A lot of them are real sharp and talk about real gutty issues, but The Gate doesn’t attract them. Young teen-agers aren’t interested in sitting around listening to folk singers. What they want is a rock house—a nice dance place. All we’d need to start one is an empty warehouse or auditorium with a jukebox and soft-drink machine. No chairs, no tables. no overhead. Psychedelic light shows maybe, and let them rock out. Young kids have a lot of stored-up tension and dancing is still the safest way they can work it off. But churches tend to back away from this fact.”

BRUCE got up to greet the red-bearded folk singer, who had walked in with a gallon jug of clear red sassafras tea hanging from each forefinger. The minister wrote him out a check for it, and they talked for a few minutes — debating whether it was anger or hate that Christ felt for the money changers when He drove them out of the temple. The bearded man said he thought what’s wrong with most Christians is “they won’t decide what they’re against and then take a public stand against it.” Bruce said, “I’m just not as much of a revolutionary as you are, but I do believe in Christian action.”

Then he was called to the phone I couldn’t help listening: “You want a real hippie or somebody who looks like one” . . . Right. The Marietta YMCA, next Sunday night. I’ll see what I can do for you.”

He hung up and grinned. “It’s gotten so part of my job is booking hippies or bearded folk singers for churches, schools and civic groups. I’m a sort of rent-a-hippie agency except I don’t get paid. If an MYF group asks for somebody to perform and tell about our ministry; I send one of The Gate’s folk singers, or an art student who puts on light shows he films himself, or this kid who makes and plays vagabond instruments. But if they want a real hippie, I go out to the crash-pads and find them one. Hippies like to talk about their thing. Besides, they’re usually hungry, and churches have good suppers. Anyway, I went to look for this certain kid a few weeks ago and he’d just cut his hair. I said, ‘Look, they want a hippie in full costume, right” What kind of impression you gonna make, man, with that short hair?’ He said he could borrow a wig. When his audience got to asking why he had long hair, he took off the wig and said, “What’s that again?’ “

ONE thing you learn at The Twelfth Gate is that it takes more than long hair or a beard to be a hippie. A folk singer said he wears one “because I happen to have a very fat face and besides it’s easier to get a singing job if you have a good growth.” A Gate waitress said some of the guys are just too lazy to shave, or want something to hide behind Roger Swanson, who looks like straight out of the Bible, has just always liked beards.

“I got out of the Marine Corps on Nov. 6 last year,” he said, “and Nov. 6 was the last day I shaved. At first I was very paranoid about the beard. I didn’t like being considered a hippie and it was hard to get an apartment. Some of the hippies do skip out on rent. You can’t blame the landladies. But it’s not hard to get a job with a beard, by the way—not in Atlanta, not if you do good work. I’m a carpenter’s helper. I also write poetry. I went to college for five years before the Marine Corps. But I’ve just gotten interested in this writing thing, also in photography.”

Roger often emcees at the coffeehouse – introducing the poets and folk singers, reminding patrons that the waitresses work for nothing except maybe $2 a night in tips, “so please cross their palms with silver when you say thanks and we have church here on Sunday afternoons at 12:30. Church does take the drag out of Sunday, so come on over.”

The Coffeehouse Church is called a “ministry” by the Methodist’s North Georgia Conference. It’s not a full-fledged church yet in the sense of a membership roll, but the kids are hoping it soon will be. Besides Sunday services, it has all the Methodist trappings, including a budget ($27,500 for next year), an official board and committees for finance, worship, programs and social concerns.

The social concerns committee ran a tutoring service for children in Vine City last summer. Two boys go to East Lake Methodist every Saturday to help with a recreation program for 270 colored children. Four of The Gate’s folk singers go on tour, booked for Methodist Youth Fellowship meetings and openings of church coffeehouses. The kids have now started a fellowship supper on Sunday nights, with ministers, politicians, city planners, lawyers, doctors, sociologists and other specialists who discuss the needs of the young people in the 10th Street area and help decide The gate’s best course of action.

As a result, the coffeehouse now has an employment agency and a free medical clinic.

“Our kids man the waiting room and screen all the patients,” said Bruce. “The clinic is now open every Monday and Thursday night at First Presbyterian Church with psychologists for counseling and doctors and nurses supplied by the Fulton County Medical Association. We had a clinic last summer in my office at the coffeehouse, with just one doctor, man, and we couldn’t take care of all the patients here.”

The Twelfth Gate began a year and a half ago at Grace Methodist Church, when Bruce was an assistant pastor there. It was Grace’s effort to “do something” for the non-churched young people in the downtown community.

Diane Smith, a beautiful girl with hair to her waist, had sat listening while Bruce talked. “I was one of the original weirdos who came to The Gate when it was at Grace,” she said. “In those days none of us kids worked. We talked all night and slept till 3 in the afternoon, and if you worked, you missed out, right? I got in a real bind with money. I’ve been through the starvation bit, the having-your-gas-turned-off bit, the corn-meal boiled in water, you know, with days of nothing. and then one of the boys would earn $5 singing folk songs or a girl would wait tables for a night, and then we’d buy potatoes and a cheap roast and cook it at my apartment. I’ve had a straight job for some time now and I’m out of debt.

“But back to our weirdo days. We used to wish so much,” said Diane. “that we had a nice place to go. One night somebody said a minister had opened a coffeehouse over on Charles Alien Drive.

Oh, right, a minister has opened a coffeehouse. We shrugged it off. Then a handful of us went over to see. It was just a six-room old house with no atmosphere, and the folk singers weren’t hired. Mostly they were those of us who could sing. But Bruce was marvelous. Just nice. We kept going back and taking our friends, and after the place closed at midnight, Bruce and his wife would come to our apartment and 30 or 40 of us would talk all night.

AT Grace they all assumed we were hippies on drugs, of course. I don’t say to the potheads, hey, I’m going to hate you for taking the stuff, but I don’t want to be around them. What’s so great about watching a kid on LSD giggling like a maniac while he crawls around on the floor, talking to dust, and then going wild remembering the awful things people have done to him, and getting crazy for revenge. It’s horrible and repulsive. And what’s so great about seeing a girl who has everything going for her get so messed up on drugs she loses her job and her friends and all she’s got left are hippies like herself. Last time I saw her she was under acid and could see her self down in a soft-drink can just a tiny little person down in a can.

“Anyway, at Grace they put out all this effort to get us and then they didn’t know what to do with us. The coffeehouse was so successful we were spilling out into the yard — maybe 300 kids a night, and some of the neighbors were complaining. We got the idea we were less welcome and Bruce was getting more and more criticized, right? We thought, if the kids went to church it would show the members that Bruce was doing some good, you know, so about 20 or 30 us went to a pre-Easter service last year. Catholics, Jews, Baptists, Methodists. nothings. The guys were clean and dressed up in suits and had their beards trimmed, and the girls put on dresses, right? We sat in the back, you know, and everybody was nice to us. but like we had this feeling we’d made everybody uncomfortable. Maybe the embarrassment was all on our part, but we could see them thinking if a bearded long haired type joined the church or the choir, and that TV camera zoomed in on him, people watching television would say,” Goodness, look at Grace” Right?”

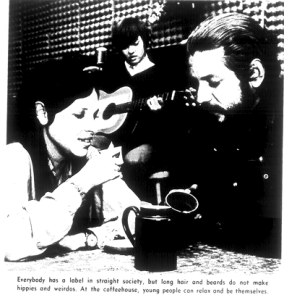

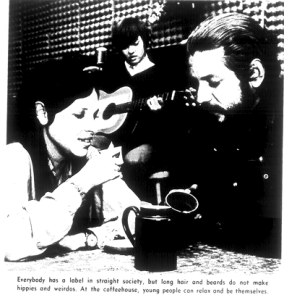

“FOR just this reason.” said Bruce. “I get more and more convinced that churches need to specialize. A minister who invites everyone in the TV audience to ‘come worship with us next Sunday’ might get a shock if they all did. It wouldn’t work, not because of snobbery or prejudice or hypocrisy. but because people who look or feel different aren’t comfortable. Everybody has a label in straight society. A boy holds a cigarette in an effeminate manner, he’s called a homo. Maybe he is, maybe he isn’t, he’s branded all the same. A guy has a beard. He’s branded a hippie, though he may have a very straight job. A girl has her “hair long and wears levis and paints pictures, she’s a weirdo. Eggheads may be respected these days, but a boy who’d rather write poetry than play or watch football is looked upon with suspicion. And there are some young people who, let’s face it, just aren’t very attractive on the surface, though they may have a depth and sincerity and loyalty you rarely find in the typical frat house or MYF group.

“The beauty of a coffeehouse is that you can expose people of all types and backgrounds to each other. With the candle light and music and coffee they relax, open up and be come themselves. Things seem more real. They don’t have to wear masks, or pretend what they don’t believe. They share a sense of belonging, and I am absolutely convinced that the need to belong to somebody is the most basic need of human beings, more basic than the need for food or sex or creativeness.”

“The kids who came to The Twelfth Gate when it was at Grace were so hungry for deep friendships they could forget food. The strange thing that happened there was the way all of a sudden, after four or five months, without my giving them any lectures about loafing, those 30 or 40 self styled weirdos started hunting jobs. They had begun to see that life is more than having friends and talking all night, that it matters to have some reason to get up in the morning. Some cut their hair and beards some didn’t. Nearly all went to work.”

Most of them were committed Christians and felt that Christ was alive in their lives says Bruce. “but they didn’t feel they had found a way to live for others. Then the kids decided to start a coffeehouse right on 10th Street, so others cotild have the chance to find themselves—the way they had at the Grace coffeehouse. The Methodist North Georgia Conference gave me the assignment, provided we’d held regular worship services.”

So The Twelfth Gate opens its door every Sunday as The Coffeehouse Church, when they aren’t having a preach-in at Piedmont Park. The kids sit in twos and fours around the tables for the sermon—drinking their coffee and smoking their cigarettes, dressed more like guests at a costume party or a come-as-you-are than like a congregation.

The Sunday I went, what made me feel “at church” was the rapt silence, the atmosphere of spiritual seeking. All eyes fastened on the Rev. Donnelly as he talked about Christ having to hang on the cross because of people’s hang ups, or quoted a priest who once asked, “Who can look up at the crucifix and say, ‘All this you have done for me and I don’t care?”

Not many churches could advertise a Sunday service that lasts three or four hours and hope to have anybody come, but that’s the way it is at The Twelfth Gate. Always after The Word comes what they call The Word Shared— something like a bull session, something like old-time Methodist testifying.

When I was there, as soon as Bruce got through with the sermon and the final folk hymn was sung, a girl at a back table said, “I’ve sinned, and I know it, and I’ve asked God’s forgiveness, right? But maybe God is like my father. I respect my father and I love him and I’ve hurt him so much. But I just can’t tell him. I just—-” She struggled for self-control. She had arrived in Atlanta the week be fore from Massachusetts. “I mean he thinks I want some thing—food or clothes or money. What I want is his love and understanding? But he just says you’ve done what, you please—and I have—so don’t come asking me for forgive ness now.”

“I guess your dad has hang ups of his own,” somebody commented.

“I know how you feel—I’d never ask my father’s forgiveness,” said a student type in suit, white shirt and tie. “I’m sure he’d just say go to hell. Let’s face it, parents really suffer when we do wrong, and it would be the right thing to apologize, even if the apology gets thrown in your face. But it’s hard to be glad about doing the right thing if you’re crying.”

“Every time I come here,” a girl near me muttered to her friend, “we get hung-up on forgiveness and the generation gap. No matter what Bruce has talked about.”

THE next speaker was at dashing young pirate. His beard had a sort of Sir Walter Raleigh trim, he wore one gold earring, his long hair was held neatly in place with sun glasses, pushed up from the forehead, and I tried hard not to assume he was a hippie just for looking like one.

“If there is this God that’s so Almighty and can do anything,” he began, “why doesn’t He answer when I ask forgiveness? If I offend her” — he nodded to the girl beside him— “she’ll forgive me the minute I ask her to and then every thing’s all right again. God is a lot greater than she is, but all I get from Him is silence.”

He was answered by a rather small young man with a hearing aid. wire rimmed granny glasses, cowboy boots and a mild manner. He spoke calmly: “What do you expect? Is God supposed to put on a light-show in your brain or send a message fluttering down from Heaven? When you’re not feeling holy, when you’re restless and incomplete, when the day is not beautiful, when somebody smiles and you say. ‘Go away, you bother me,’ that’s what it’s like to be unforgiven and separated from God.

“God to me is love,” he said. “I know I’m forgiven when I feel turned-on to Him, holy, with no hang-ups. It’s just a total sense of peace and relief and release from guilt.”

Not all ministers think a coffeehouse like The Gate is a valid way of reaching out to those not attracted by the established church. Though many in the Methodist clergy are enthusiastic about what Bruce Donnelly is doing, at least a few doubt that it is valid even as an experiment. They think church coffeehouses are a passing fad, like the hippie thing, and too far out from “the true vine” to change any lives.

MAYBE, maybe not. The doubters should go see for themselves.

All I know is that I like the picture of 40 or 50 young people working their hearts out for a dream, most of them without any pay, and then freely giving away thousands of hard-earned dollars in the name of the Lord.

I know I was deeply moved by the folk singers at the Sun day service, impressed by the young minister’s sincerity and positively electrified when that young man told what it’s like to feel holy.

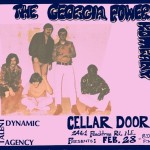

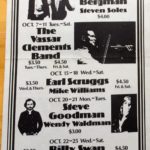

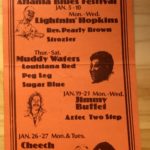

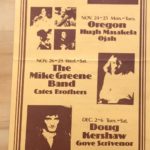

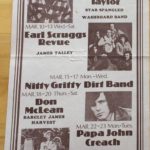

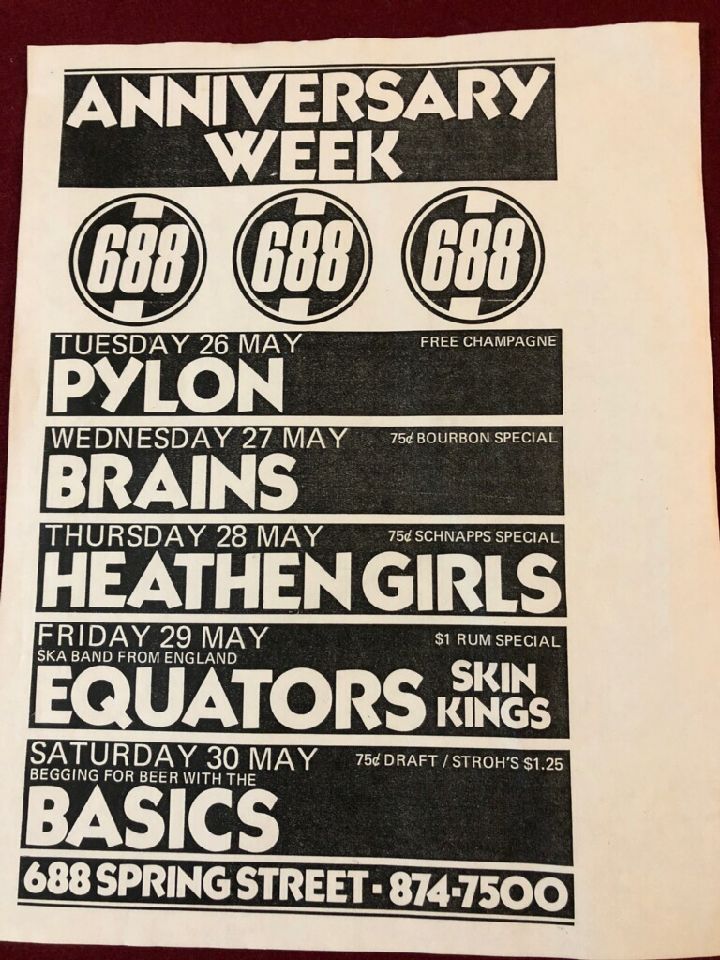

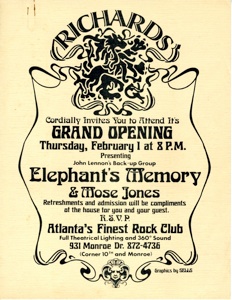

Alex Cooley opened Atlanta to the music world, and vice versa. He also brought MidTown Music Festival to The Strip!

Alex Cooley opened Atlanta to the music world, and vice versa. He also brought MidTown Music Festival to The Strip!